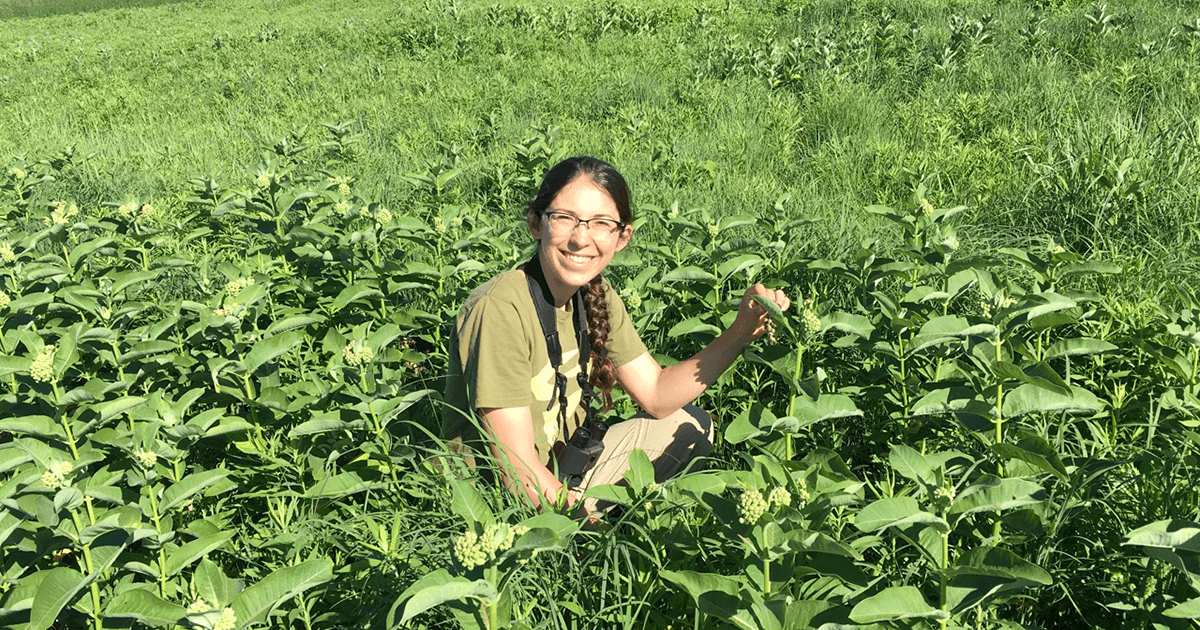

FMR Intern Allie's favorite insect sightings

This spring, I graduated from the University of Minnesota-Morris with majors in biology and environmental science. Entomology was one of my favorite classes, but I've been fascinated by insects ever since I was a kid. When other children screamed, "Eww! A bug!" I came running to investigate.

However, insects are not only wacky and beautiful, they're also in peril, which is one of the reasons that I hope to study them in the future. A 2017 study in Germany found that insect abundance has decreased by over 75 percent since the 1990s. FMR has written about why this is concerning — a third of our food relies on pollinators, a service worth $57 billion annually, which pollinators do for free. In addition, insects are an essential link in the food chain, and as insects decline, the birds and fish that depend on them for food are suffering as well.

How I found FMR

My journey with FMR started back in high school when I began volunteering at FMR events with my dad. Now, I'm thrilled to be working as the field ecology intern this summer, where I can contribute to insect conservation efforts along the Mississippi River.

This summer, I'm leading volunteers in community science projects to monitor monarchs, pollinators and soil insects. These projects can help researchers understand how insect populations respond to changes in habitat and how they utilize plant resources, which can then inform restoration practices in the field.

Globally, the greatest threat to insects is habitat loss — both in quantity and quality. FMR's conservation work protects habitat for species like the federally endangered rusty patched bumblebee and for less charismatic insects like robber flies.

Restoration of degraded habitat is also important because some insects like the magnificent dogbane leaf beetle (Chrysochus auratus) below require specific plants in order to complete their life cycles. In addition, non-native plants sometimes contain toxins in their nectar or are less nutritious than native plants.

What I've found so far at FMR's restoration sites

In the field, I'm always on the lookout for new and interesting bugs. I've found that the best way to spot insects is to look closely at plants and check them from different angles. I keep my phone handy to take photos, and I've been using the Seek app through iNaturalist to identify unusual finds. Here are a few of my favorites so far.

Brown mantidfly

During a pollinator survey at Vermillion River Linear Park in Hastings, I discovered the strangest insect that I have ever seen. At first glance, I thought it was a long wasp, but a closer inspection revealed front legs that folded up like a praying mantis. It looked intimidating, to say the least. I later figured out that the formidable insect was a brown mantidfly (Climaciella brunnea).

The mantidfly life cycle is about as bizarre as their appearance. The mantidfly larvae wait for a passing spider and then hitch a ride back to the spider's nest where they sneak inside the arachnid egg case as it's being formed. After feasting on the unfortunate young spiders, the larvae then undergo metamorphosis and develop into the winged adult. The adults masquerade as wasps to convince predators that they can sting, and they capture unsuspecting prey with their lightning-fast front legs.

Aetole moth

While on the lookout for pollinators, I noticed another unusual insect perched on a daisy fleabane flower. At first, I thought it was a leafhopper of some sort, but the Seek app identified it as a moth in the genus Aetole. The moth held its back legs straight up in the air, almost like it was about to do the YMCA dance. Scientists are still unsure why the moths practice this behavior. Perhaps it confuses potential predators that enjoy snacking on moths — it certainly fooled me!

A baby katydid

Baby katydids have to be some of the most adorable insects out there. I spotted this fork-tailed bush katydid (Scudderia furcata) on a milkweed plant at the Flint Hills restoration in Pine Bend Bluff Natural Area while doing a weekly monarch survey, and I've met a few more at other sites.

This katydid is a nymph, so it doesn't have fully developed wings yet, and it looks a bit different from the pale green adults that can easily camouflage amidst the plants. Katydids aren't known to feed on milkweed, so it was probably just using the plant as a perch.

Robber fly

Think this is a bumblebee? Look closer!

While surveying for birds at Hampton Woods Wildlife Management Area in Dakota County, FMR ecologist Karen Schik and I found an uncommon robber fly. This robber fly mimics the appearance of a bumblebee as a disguise. Passing unsuspected, it's able to capture beetles and bees out of the air, then inject enzymes to liquefy the insides of their prey to make a better meal.

This robber fly (Laphria thoracica) closely resembles the half-black bumblebee, but you can tell it's not a bee because it has only one pair of wings — bees have two. The wings are also much longer than bumblebees', and the eyes are smaller and closer together than a bee's eyes, which are on the sides of their head. The disguise fools predators into thinking this is a bee that can sting, even though it can't.

On a return trip to Hampton Woods for a vegetation survey, we stumbled upon a pair of mating robber flies. Once I've learned to identify a species, I start seeing them everywhere!

Hackberry emperors

Another morning when we were out surveying birds, Hampton Woods was thick with butterflies. Ecologist Karen Schik was very popular with the hackberry emperors (Asterocampa celtis), which seemed to enjoy her blue shirt, and one even posed for me on the clipboard. The hackberry emperors were also basking all over the path and flew up like a cloud when we walked through. It felt like we were strolling through a butterfly house!

As the name suggests, hackberry emperor caterpillars feed on the leaves of hackberry trees. Unlike many popular butterflies, the adults rarely visit flowers, so they're not frequent pollinators. However, they drink from tree sap, rotting fruit, human sweat and carrion to obtain salts and nutrients. The weather conditions must have been ideal for the hackberry emperors this year because clouds containing thousands of these butterflies have been spotted in Wisconsin as well.

Pollinators

When people think of pollinators, honey bees are often the first image that pops into people's minds. However, honey bees aren't actually native; they were brought to North America back in the 1600s. Minnesota has over 400 native bees, which vary widely in size and color, ranging from giant fuzzy bumblebees to tiny metallic green sweat bees.

Bees and butterflies often get all the press about pollination, but some beetles can pollinate, too.

During a pollinator survey at Vermillion River Linear Park, I accidentally caught an action shot of a native furrow bee (genus Halictus) visiting a prairie fleabane flower.

You can tell that this is a female by the bright yellow packets of pollen on her legs. Female bees often have clumps of specialized hairs on their legs called scopa, which they use to transport protein-rich pollen back to their nests in the ground. Furrow bees belong to the sweat bee family (Halictidae), and after visiting the flower, this bee landed on my arm for a sip of sodium.

Fifteen-spotted lady beetle

Native ladybugs were once common across North America, but their numbers have plummeted in recent years. Most of the ladybugs that we encounter, like the ones that pile up in window ledges during the winter, are nonnative Asian beetles.

Before this summer, I knew that there were some native ladybugs, which are important predators of plant pests like aphids. However, I had no idea how many different species can be found in North America; there are over 50!

At Hampton Woods, FMR ecologist Alex Roth pointed out a white ladybug, which turned out to be a fifteen-spotted lady beetle (Anatis labiculata).

This native species comes in two color morphs — either white or dark purple. I'm hoping to find the purple variety someday.

Giant stonefly

As I was pulling garlic mustard plants during a volunteer event at the William H. Houlton Conservation Area in Elk River, an elegant, long-winged insect caught my eye: a giant stonefly!

Immature stoneflies, called naiads, live in the water, where they feed on algae and decaying plant material and are an important food source for fish such as trout. The naiads are highly sensitive to pollutants, so they're often used as bioindicators of high-quality water. I spotted two adult stoneflies at Houlton, which suggests that the nearby Elk River is in good shape.

Ichneumonid wasp

This wasp (Megarhyssa atrata) may look intimidating, but fortunately, she uses her three-inch-long ovipositor for laying eggs and not stinging people.

Ichneumonid wasps have a fascinating, and rather gruesome, life cycle. Remarkably, the female wasps can detect the presence of insect larvae crawling under the bark of trees, and they use their massive ovipositors to drill through the tree bark and lay their eggs into the larvae. When the eggs hatch, the parasitoid wasp larvae eat their host alive before eventually emerging from the tree as adults. Parasitoid wasps like these are important biocontrol species because they can help reduce populations of plant-eating caterpillars.

Join us

I'm excited to be making a difference for native insects here at FMR, and in the future, I hope to continue working in insect conservation.

If you'd like to get involved at these and other FMR habitat restorations, sign up for FMR's e-newsletter Mississippi Messages so you can find out about our upcoming volunteer stewardship events. You can also check out our calendar for current opportunities.